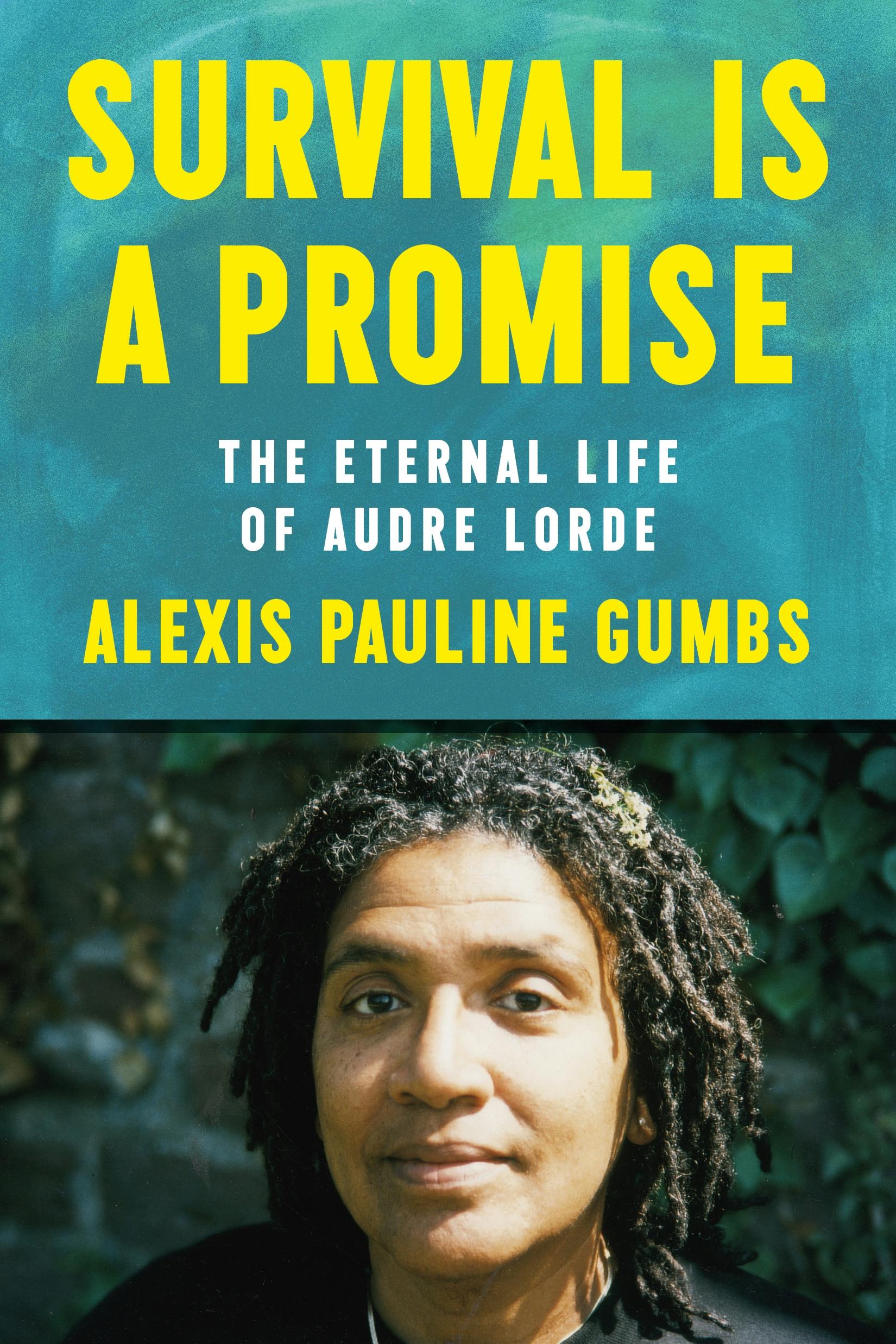

In her new book, Survival Is a Promise: The Eternal Life of Audre Lorde (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2024), Alexis Pauline Gumbs explores Audre Lorde’s deep and often-overlooked focus on the nonhuman world’s teachings on social and political liberation. As a self-described “Queer Black Troublemaker,” “Black Feminist Love Evangelist,” and “aspirational cousin to all life,” Gumbs encourages readers to take a closer look at the ecology of Lorde’s poetry in order to better understand our vital interconnectedness at a moment of global fracture.

Gumbs is a scholar, activist, and the author of several books, including Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals (AK Press, 2020), which won the 2022 Whiting Award in Nonfiction. She spoke with Lullaby Machine about slowness, online echolocation, “revolutionary mothering” as a Black Feminist imperative, and the power of lullabies in a world obsessed with sleep apps.

***

Olivia Q. Pintair: In Survival Is a Promise, you write about Audre Lorde's lesser-known poetic engagement with ecology. For Lorde, you reveal, ecological images were not just metaphors, but teachers of a Black Feminist poetics—mirrors of how "to be in relationship with a planet in transformation" as beings who are also "of earth." I’m curious if there are any nonhuman beings who have been particularly present teachers for you lately.

Alexis Pauline Gumbs: How to choose… Well lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about trees. During Hurricane Helene, some of the trees around my house fell. I’ve been thinking about their contribution and thinking about how to respect them, beyond obstruction or going into the wood chipper. We have an intimacy of breathing with trees. After going on book tour, I was home for almost two months, which was a long time for me, breathing with this particular community of trees here.

Recently, we went to Los Angeles to be in ceremony with some folks who were very impacted by the wildfires. It really hurt to breathe because of all of the debris in the air. But I was thinking about how I think part of our collective assignment,—I know for sure part of my assignment—is to try to actually be a breath of fresh air. Literally, to try to actually make it easier for others to breathe. I think a lot about breathing in Undrowned and in life in general. I feel grief around the fact that we have made so many places already unbreathable. The mentorship of the trees feels more urgent than it has been, or maybe it's just more obvious to me now, because of that experience of contrast. I offer my gratitude to the trees that surround me for how they show up, how they live their trajectories, how they become into their next life, what they have to teach me about not just breathing, but facilitating breath.

Maia Sauer: In Undrowned, you write of the power of slowness, learning from the harbor seal, who slows her heartbeat to accommodate deep dives under water. The harbor seal lives between land and sea——starkly different geographies that feel akin to the disparate time scales and geographies that we live between daily, thanks to the internet and other globalizing forces. With this harbor seal teacher in mind, what practices of breath and slowness do you integrate into your life? What helps you remain present or get closer to breathing “at the pace that love requires?”

APG: The profound range of the harbor seal's heart rate still blows my mind. I don't know if I'll ever get over it, really. When I share that piece, I do an exercise with people, where we see how long it takes for us to perceive sixty heartbeats. It's all different times for all of us. It's usually fastest for me, because I'm facilitating, and I'm, like, terrified. I think no one can tell.

I just came back from the gym before this conversation. There are heart rate charts there and people have special watches where you can check your heart. People in that context are so conscious of their heart rate, and I kind of resist that. I don't know. I'm not necessarily here to do the math of my heart rate. But the harbor seal has really inspired me to just notice, in non-precise terms, the range of my own heartbeat and where it changes and where it becomes noticeable to me without me intentionally being like how fast or slow is my heart beating here? What does it feel like in this space?

For me, the slowing is always possible, but there are types of spaces that, inherently, I have a response to, in terms of a heightened heart rate or slowed heart rate. That's information about what it is to be in those spaces. It could be that I want to avoid some of the spaces where I have a high heart rate, because I’m stressed out in those spaces, or feel afraid or defensive in those spaces. But there's also the possibility of slowing my heart, even in a space like that, through breathing. Sometimes I'll sit on my hands. Sometimes I’ll count breaths, pause breaths. Always when I'm facilitating, I start with breathing. It is, for me, a way to slow down into the space and expand the listening. Maybe it expands time. It definitely slows the racing of my mind when I do that.

OQP: As Lullaby Machine has come together, we’ve spent a lot of time thinking about the implications of imagining lullabies as gifts that strangers could offer to each other. Your writing about revolutionary mothering has been integral to our thought process with this project. Could you talk about what “mothering” means to you, and how you’ve engaged with that idea in your work?

APG: The way I engage with the idea of mothering is really shaped by Black Feminist literatures and theories of mothering. It's a huge theme of Black Feminist writing, thinking, and activism, since even before it was called Black Feminist writing, thinking, and organizing. Mothering, in this context, is grounded in the dignity of care, in respect for our inherent interconnection. I think especially about the way that Hortense Spillers has written about mothering. The clarity of mothering as a Black Feminist imperative shows up at the site of violence that denies the dignity of care and our inherent interconnectedness. For me, mothering is all the things that Audre Lorde says it is in Eye to Eye. It's faith. It's pouring into a possibility without knowing what the outcome will be. It's rigor. It's attentiveness. It's a multi-directional possibility in every moment.

In my work, I'm always looking for mothering that may not be named normatively as mothering. Part of what Hortense Spillers, Rickie Solinger, and many other theorists write about is motherhood within patriarchy——within an antisocial, neoliberal capitalist frame that seeks to make invisible, more easily extract, and penalize forms of care. These sites of our abundantly-evident interconnection aren't convenient for a capitalist project or a patriarchal future. Caring for the people who are doing so much of that care work, and honoring the leadership of people who are doing care work, is completely necessary. If we were already doing that, we would all be having a much easier time. All of us, of every species. But I like to believe it's not too late, and that it's something we can practice today.

MS: We’ve been curious about the power of lullabies to soothe and comfort, even while many traditional lullabies use haunting language and dissonant melodies. I’d imagine you remain keenly aware of the role sound plays in crafting the tone and texture of your work. How do you relate to sound, as you write?

APG: I was just doing a workshop last night, where we were focusing on a particular part of Survival Is A Promise and Audre Lorde's childhood nightmares. And I was like, of course she was having nightmares. When you read the nursery rhymes, when you read the bedtime stories, it's like, this is so terrifying. A lot of children die and disappear for unknown reasons. How is there anything but nightmares?

But to acknowledge it——I agree with that. Sound is really important. Sound, rhythm, language, is a vibrational technology. I was talking about this the other day, with this an artist named Zahra Malkani, who does reparative sound work with lullabies. We both have been part of this Ways of Repair collaborative that's about thinking about reparations for climate colonialism, beyond the way that the UN thinks about it right now. Zahra and I were talking about how instructive the actual work of supporting a baby to go to sleep is in terms of the energy work of it——the vibrational understanding of it. At least in my experience, I have to slow my heart. I have to be intentional with my breathing. My energy has to become conducive to someone else moving into the space of sleep in my heartbeat radius. Talking about that explicitly with her was really great preparation to be talking with you all.

Before I really started thinking about my work with language as vibrational work, I always related to it that way. Even in high school, I always read my work out loud to myself. It's always a question of is that the sound? And until it is the sound, you’ll never get to read it. That's just part of the rigor of my process. Because I know that if I read my writing to you, I might be able to communicate the feeling I want to communicate through the vibrational work of reading. But I have to depend a lot more on the poetic possibility of words on a page if I'm not going to be there to read it to you. Now when I hear other people read my work, it really does sound vibrationally true to me. I recently had that experience with the translations of Undrowned. It's very interesting to hear someone else read my work in another language and still recognize the vibration I put into it.

So all that means that the work I put into the world can't reproduce violence, even though it often talks about violence, or sometimes is responding to violence. While I’m writing, I'm practicing on myself about whether my writing feels like love or not, and when it does feel like that to me, I'll share it with you. It's similar to the lullaby moment of supporting somebody in their rest. I am attuning myself to what love feels and sounds like for me, through my accountability to you.

OQP: In Undrowned, you write about the Indus river dolphin, who uses echolocation to communicate to others living in the ocean. "In the language I was raised in," you write, "“here” means “this place where we are,” and it also means “here” as in “I give this to you." You go on to ask what this dolphin's communication pattern might have to teach those of us living on the internet: “Could I learn from the Indus river dolphin a language of continuous presence and offering?...Could we learn that? We who click a different way, on linked computers day and night?”

I'm wondering how you relate to the digital world these days. Have you found online spaces of "continuous presence and offering?"

APG: I have a lot of rigor in terms of the way that I relate to digital space. It's an amplification space, especially as it's structured now in the form of social media, so I am really, really specific about the fact that I do not use online spaces to rant. Things that I need to say but I don't want to grow, I don't say on the internet or in my published work. I say those things to somebody I trust, and we're venting. We're releasing it. We're not trying to give it more energy, because we want something else. Mostly at this time, I use digital space for offering.

Before social media was really social, blogging spaces were a huge part of my coming of age, and of my community-building beyond my direct geographic region. Still every day, I'm in communication with the same radical women-of-color bloggers who I met during that time, some of whom I've gotten to meet in-person. I want to speak to the gratitude I have for this. It’s almost like a sonar situation. In our specific geographic areas, there are roles that we each play, right? I have a certain role, but no one right where I am has the same role as me, which is as it should be——they got their roles, and I need them to be who they are. But with the breadth of space that the internet offers, it's like, oh, but here is this person who has a similar role to me in her own community, and how amazing it is for us to be able to support each other. To be like, are we doing it? Maybe we could do it better. Maybe we could just cheer each other on. That's so huge.

In the Indus River context, it's a pretty murky river. The walls of the river are a lot of what the Indus River dolphin is echo-locating through. But sperm whales, for example, are hearing each other across literally the whole planet. I think about what our human connection on the internet is actually for. I don't know if it's a form of noise pollution for our digital connections to be so deeply monetized. If that's the noise that is unfortunately separating sperm whales from their families because they can no longer hear each other. I’m feeling like there's something about the current status of the digital spaces that I have access to that doesn't honor what I think is the best possibility for how connected we can be across space at this moment in history.

MS: You’ve spoken of your decision to name yourself relationally, as an “aspirational cousin to all life.” What power have you found in this naming? What do we gain as relational beings by speaking explicitly in this way?

APG: All my relations, all my relations.

It is important, I think, to say explicitly what could otherwise be obvious, but instead is sabotaged by imposed systems that teach us that we're individuals, that we're separate, and that we should actually aspire to be self-sufficient, even though that's not a thing on earth. It's not an ecological possibility to be self-sufficient. I already have the tendency to be like, how are we related? I know that we're related. How are we related? But I also don't really need to know how we're related, because I know that we’re related.

Calling myself an “aspirational cousin to all life” is a statement of the ethic that I'm living inside of, which is: you're my relative, so I should treat you accordingly. And also a reminder that I'm your relative, so you don't have to feel like you're an isolated person, and you don't gotta treat me like how an isolated person treats people. It's really important for the permeability of so-called species to say, like, okay, this tree fell. This is a relative falling over. It's not just out of context. Honor matters. I feel like all my relatives deserve honor. I think that it's a practice of putting that into the world.

More obviously, I put it in my bio. It's the thing that people have to read out loud when I’m in a space. The bio is such a space for individuality. It's for the manufacture of the self. It's for accomplishments. I gotta put that context in there too, for whatever reason, but I think the most memorable thing ends up being the relational piece of it. It’s also just its own, small poetry project of mine.

OQP: Lullabies are maybe most famously sung to children just beginning their lives. I’d love to hear your take on the role of lullabies in the context of your work as a doula.

APG: I think the intergenerationality of lullabies is important. It's something——again, shout out to Zahra——that facilitates the question of: Well, what do we want? What do we want these new people to know? What do we want them to know first? In the tradition Zahra studies, a lot of names of ancestors and lineages are incorporated into the lullabies. It's like, maybe we want you to know who you are in the context of the people who came before you, who don't get to meet you. I think there is intimacy there. There's that intersubjectivity that I was talking about. You can't really support someone to go to sleep while being all raucous within yourself. You go with them into a peaceful state. You generate a peaceful state within that could be shared. That's part of the reason it's so great that you all are doing this work. If we could all generate a peaceful state of being, think about how different that would be.

It's a beautiful thing to know that every culture that I've known about has a practice of this. There are people in every community who know how to do this, and it's not hard to find them, because everybody needs them. You need the ones who are good with babies, or else nobody will sleep. It doesn't look like it on the surface, but this is a society full of people that, in every culture, have a practice of generating peace. It is only because of the systemic disempowerment of the people and the labor that holds that treasure that we don't have access to it as our full reality at every moment.

MS: Have you been turning to any particular lullabies for comfort lately?

APG: I think about the singer, Laura Mvula, as a purveyor of lullabies. I don't know if she thinks of herself that way. She has this song called "Sing to the Moon," which is a song that I go to for my heart. It is a song that is specifically speaking out to someone who's going through sorrow, and encouraging the person to sing to the moon, towards their healing. I relate to that as a path to peace for myself, for sure. Sometimes it's a path to peace through feeling my own sorrow more deeply, and I really appreciate that.

Other songs that I've used as lullabies really have just been songs I can remember in a given moment. Songs released in an acoustic version. I used to use the hidden track from Alanis Morissette as a lullaby for my cousins when they were little. I usually read my partner to sleep. Usually fiction. We're reading Justin Torres's, We the Animals, and oh my god, it's so beautiful. Talk about vibrational care in the craft of all these tiny stories that make up this novel about this family. It's incredible. I guess it's weird to think of any of those things, really, as lullabies, especially Alanis Morrissette, and the great novelist Justin Torres. But I do think of those as lullabies.

OQP: We've been talking a lot about lullabies as a form that can be really amorphous. So I love the idea that reading a story could be a lullaby, or Alanis Morissette. All of that feels very fitting.

APG: I do think it's a strange time. There are sleep apps now. There’s this whole industry trying to help people sleep, which is also fueled by the same industry that’s stressing us out. I'm really curious about what your different conversations will show us about the possibility of lullaby.