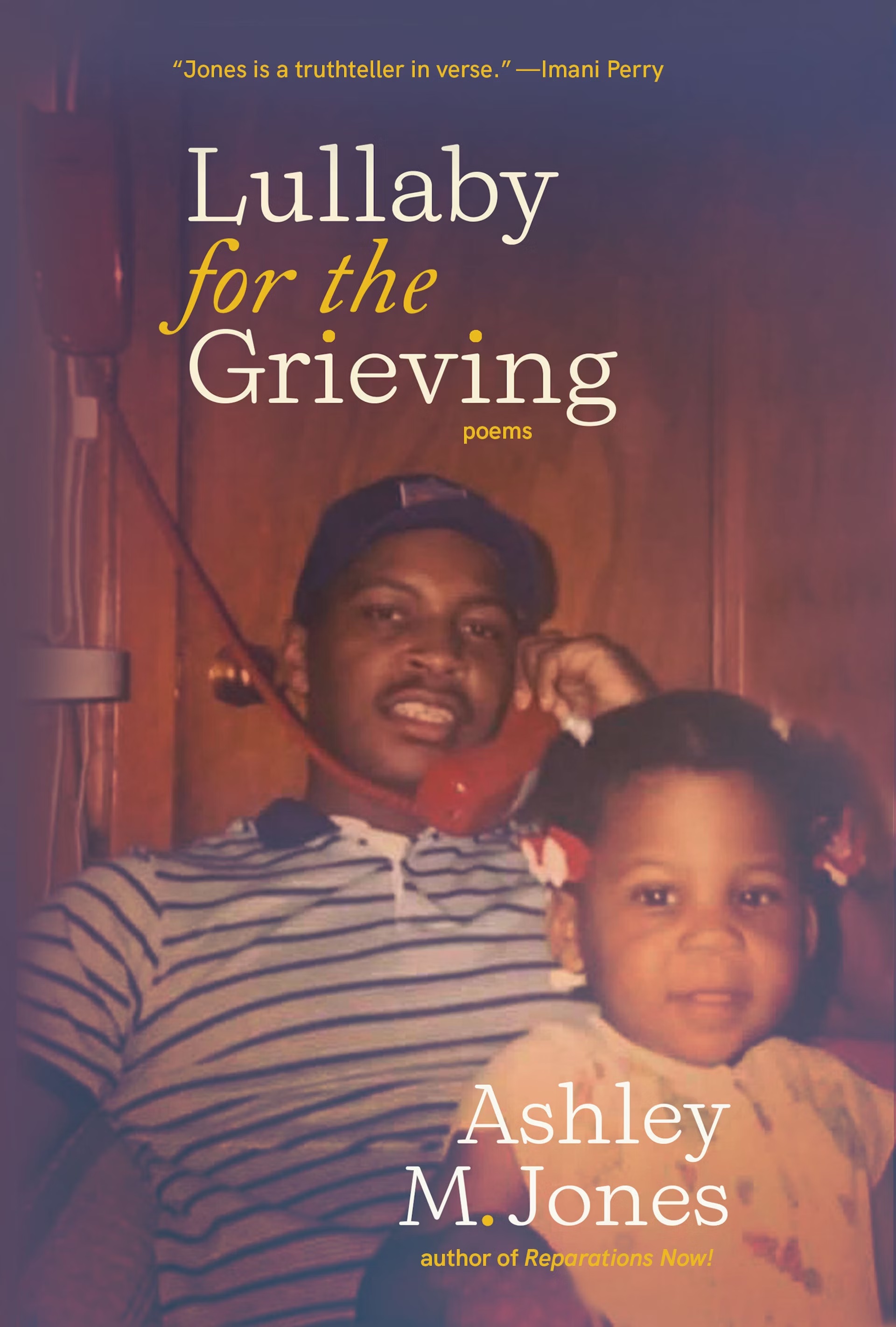

“the soil remembers the names of our mothers/ our fathers/ even the babies who/ made their first and last milkbreath and went to heaven,” writes Ashley M. Jones in her new poetry collection Lullaby for the Grieving (Hub City Press, 2025). Animating landscapes from the Underground Railroad, to her father’s backyard garden, to the wilderness of the body, Jones studies the overlapping edges of grief, twining personal and ancestral memory into a kind of choral lullaby.

Jones is the Poet Laureate of Alabama (2022-2026) and the award-winning author of four poetry collections, including Magic City Gospel (Hub City Press, 2017), dark // thing (Pleiades Press, 2019), Reparations Now! (Hub City Press, 2021), and most recently, Lullaby for the Grieving. Her debut essay collection, What the Mirror Said: The Necessity of Black Women in Poetry, is forthcoming from University of Michigan Press in April of 2026.

Jones and I spoke about dissonant lullabies, the page as a place, leaning on form, and what it means to make “doorways/ out of our voices in the air.”

***

Olivia Q. Pintair: I want to ask about your relationship with the word lullaby. What is inside of that word for you? What brought it to the center of your book’s title?

Ashley M. Jones: I didn’t know that this book was going to be called Lullaby for the Grieving until I wrote that titular poem. I had just done a pretty serious hike for a poetry workshop with Palavi Ahuja, who had prompted us to write a lullaby. I like nature. I like looking at nature. But I'm not a big deep-woods hiker. At the end of this hike, I was sitting by the Sipsey River, full of bug spray and sweat. While responding to the prompt, I wasn't really thinking about lullabies I had heard. I was trying to think about something that people need, something that I needed at the time. Once I finished writing the poem, the title seemed clear.

All of us are going through multi-layered grief. All of us experience personal grief. There are constant opportunities to feel grief. For me, a lullaby is not necessarily always a pretty-sounding thing. My mom used to sing us lullabies, but she's a terrible singer, so they were very dissonant lullabies. But the sound of her voice, no matter how melodic or not melodic it was, was calming. In the same way, a lot of these poems are not about happy things or pretty things. The poems themselves are not always soothing, but somehow recognizing the grief and working through it is what helped me.

OQP: The poems in Lullaby for the Grieving conjure and animate so many different landscapes. How did you relate to place while writing this collection?

AMJ: Place is super important in my work, and it has been for a very long time. I've been writing since I was seven years old, and I'm 34 now. Place began to play a really big role in my work when I was in graduate school, getting my MFA in Miami. I missed the south. I know Miami is more southern geographically, but it is not the same. I missed the deep south so much that I started to write about Alabama exclusively. Everything I wrote was trying to get me back to my home. That's when I really started to become a place-based poet.

Part of my goal in writing is also to tear down some of the binaries and barriers that we place around what we call history. For example, we often say there's a past, a present, a future, but all of those are intertwined. We say that there's above the Mason Dixon and below the Mason Dixon. It's not a real thing. All the same ideas exist across the places of this country. And even from body to body. We all have our own bodies, but there are so many more connections that we could make if we got past those barriers.

Even thinking about the page as a place is really important to me. As an artist, I should feel like the page is infinite. I don't have to be confined to a left-aligned, lineated poem. I can make other shapes, because I'm making art. It can be fun. It can be surprising. All that is to say that I try to let myself go anywhere. We put so much stock in barriers, or state lines, or county lines, or property lines, whatever. But those things are all invented. Usually, they're used to create more division.

OQP: Lullaby for the Grieving is present to many sources of grief——from the death of your father, to the violence of the Middle Passage, to the blurred and shifting landscape of heartbreak as it lives in your speaker’s body. The collection is also punctuated with several poems called “Grief Interludes.” How did you approach writing about grief on so many scales?

AMJ: I didn't know the book was going to be about grief when I was writing what I call “typical Ashley Jones poems,” which are usually about being Southern and Black and about history and America. Those are the ingredients that you're probably going to find in every Ashley Jones poem. It wasn't until my cousin passed and my father passed, one year after the next, that I really started to write intentionally about grief, because that's what I was facing. It was also the pandemic. There were other types of grief that were happening. I didn't know that I was going to approach any of this as grief until the someone died poems began to come. At that point, I was able to see that these other poems I had written were also about a type of grief, but I just hadn't named it that yet.

Since writing about grief is more emotional for me, I sometimes have to trick myself into being able to do it. For example, in “Snow Poem,” the form itself is what dragged me through writing that poem. I had to stop so many times, which is unusual for me. I'm a pretty fast writer, usually, but I could not do that in one fell swoop. I was either crying or it was just that my brain couldn't do the memory anymore. Or the flashbacks were getting too vivid. In terms of the “Grief Interludes,” those just came when they came, just as the grief comes whenever it wants to.

Writing grief is similar to my normal process, in that I just let the poems take me where they want me to go. But I also have to be very careful with myself, because this is very difficult material for me. I write about a lot of difficult stuff, but with the death of a loved one, for example, there's the added layer. In one of my last books, I wrote about Mary Turner, who was lynched very violently in Georgia and had her unborn baby cut out of her stomach while they were murdering her. That story is very hard for me to read. Somehow, though, I was able to work through it in a way that I couldn't quite work through the reality of my own father being gone. To write about the grief that is closest to me, I had to recognize that I am a person, and not just a machine of processing.

OQP: In “Home: Variations,” you write: “Remember how we, unmoored,/ made our own bodies a home, made doorways/ out of our voices in the air…” I love the image of a voice as a doorway, and the idea that breath and sound can become a kind of portal. That really resonates with how I think about lullabies. I’m curious if you have any particular memories of encountering a voice (spoken or on the page) that became an important doorway for you.

AMJ: I'm thinking of so many voices right now. I've been thinking about this a lot for my PhD, so let me just warn you that this is about to be a nerd-out moment.

I've been doing some writing about the way that Black people have used English since we've been here in the United States. Even though African American Vernacular English is recognizable as English, there’s a particular way that we have [transformed] this [language]——which was both forced upon us and also forbidden to us, since it was illegal for us to be literate——into something that feels like what we may have come from. There's research that says that AAVE has some of the same grammar patterns as African languages. It’s incredible to me that a people could remake their home in a new language. That blows my mind.

In my own life, many voices are coming to my mind. My grandma, my mom's mom, had this very particular voice. It was a little bit shrill. There’s this beautiful way that she used to laugh. Whenever we would leave her house, she would always say, I enjoyed y'all. But it was in a certain tone. Everyone in my family can do her impression and it automatically takes us back to her. My boyfriend also has a very particular laugh. Every time I hear that laugh, it just makes me feel warm and fuzzy inside.

Now that my dad has passed away, it’s also really special whenever I'm able to hear his voice in a recording. When somebody's gone, it's hard to recall anything. I think maybe science tells us that we actually can't store the faces of people in our minds. I can't always make his face or hear his voice inside of my head, but when I hear it outside of me, that takes me back.

Sometimes even just the tone that people use can be a doorway. With African American Vernacular English, for example, it's often just the tone of how something is said. This is also true for Southerners. There's a Southern way to say anything that’s just not the same in other parts of the country. Even other people saying y'all is not exactly… I would never go against my New York friends who say y'all in their New York way, but it's in their New York way. It's just not the same thing.

OQP: One idea that underpins Lullaby Machine is the understanding that (as Tricia Hersey puts it) rest is a kind of resistance, especially in the context of extractive racial capitalism. I’m curious what your personal relationship with rest is like. Is there a relationship for you between rest and poetry?

AMJ: Trisha is a queen. Truly. I want to follow her advice much more than I actually do, but it’s hard, because we are part of this system that values us because of our work. I am actively trying to understand how to prioritize rest and how to not feel guilty for taking rest, because I do. I feel very guilty when I'm not doing something, because there are so many things to do. I have a job. I have a poetry career. I run a non-profit because I'm crazy. I have a family, I have a boyfriend. I'm in school getting this PhD (because I had extra time, you know). I want to live my life, but also… where is the time to just sit and be?

The other side is that I am making these choices. Some of the choices are mine. I didn't make the choice to be born into a capitalist society. No, I did not. I didn't make the choice to be a Black woman, although I’m grateful that I am. It's awesome. But it’s also true that in this country, and maybe others, Black women are put upon in ways that other people just aren't. Sometimes it's hard to articulate how that's true, but we know, living in our bodies, that it's very, very real. A lot of different types of labor are put on Black women. So as Trisha says, it's very important for us to rest, because that is a form of resistance, and it keeps us able to do the meaningful work, which is not necessarily the work that the system wants us to do.

In the middle of writing a poem, I do often find a space——it's not exactly rest, but it is a space to take everything off. To not be on in the way that I feel like I have to be. I've lived a public life for a while, and certainly for the last four years being Poet Laureate. Writing poems gives me at least some space to be totally quiet. To hear myself, to hear God, and just be very still.

OQP: I heard you say in an interview that the poet's role is to offer a mirror for society. If readers were to consciously engage with Lullaby for the Grieving as if it were a mirror, what do you hope they would see?

AMJ: That's a great question. Nobody's ever asked me that before. I think I want readers to see themselves in the mirror, but maybe a different side of themselves. Before my dad died, I couldn't see what I might look like in this particular situation. I often said——as a kid, as a teen, as a young adult——that I didn’t think I would be able to live after either of my parents died. I would always say I'm just going to go with them. There's no way I'm going to be able to live. So I literally didn't see what I could look like in this situation.

Maybe those who read this book who have not experienced profound grief will be able to see like, okay, this could be me, or it will be me, in some amount of time. For those who have gone through something like this, I hope they see me standing next to them. We're together on this journey. All of us on the whole planet.

I also hope that readers see the place that they live——if they're in the United States—more clearly. I think that too many people are looking through funny mirrors when they're looking at the United States. It can feel safe to look through a funny mirror, because things can be whatever you want them to be, but it's not useful for you or for anybody else to pretend to see something that isn't there, or to look past something that actually is there. The issues that we're seeing now in this country were not invented in 2016. I think it's important that we all see ourselves and each other more clearly. That's the only way we're going to get through any of this.